Censorship, Banned Books, Seized Mail, and ONE, Incorporated v. Olesen

ONE Magazine provided a unique forum for gay men and lesbians to discuss their lives and their problems. Further, the magazine advocated for their rights as human beings and American citizens, and appealed to their interests in culture and the arts. However, one of the publication’s most powerful legacies is a lesser-known aspect of the magazine’s history. This was the editors’ bravery in their unwavering determination to challenge the system as they fought for their rights to freedom of speech for the press.

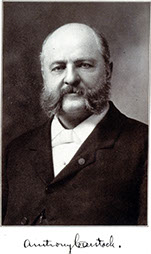

As such, they tirelessly fought against the establishment, which, throughout the 1950s, employed government agencies and the Post Office, and used censorship and obscenity laws to suppress the mailing of unwanted printed materials. This practice was long established, beginning in 1873 with the Comstock Law, named for prolific moral crusader Anthony Comstock, who, along with other members of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), founded the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV), dedicated to policing the city to root out vice. While being primarily known for opposing literary works, at newsstands, and in the mails, the society “orchestrated raids on clubs with gay performers and on shops with gay literature, reflecting concerns among the elite of homosexual activity in the working class neighborhoods of New York City, going back to the late 19th and early 20th century.

The Comstock Law’s purpose was to "prevent the mails from being used to corrupt the public morals,” and was used for more than a century as a powerful method of control for the religious and conservative right. They were determined to prevent the dissemination of information on women’s reproductive rights and health, as well as the importation of pornographic materials from abroad, and the writings of authors and publications they considered subversive. The work of groups like the NYSSV helped create a system by which federal and postal authorities could exercise great control over what was considered obscene and what could be mailed.

The ONE Exhibition,

The Roots of the LGBT Equality Movement

ONE Magazine &

The First Gay Supreme Court Case In U.S. History

1943-1958

Margaret Sanger. Undated photo. Photographer unknown. Image courtesy of Google Images.

Sanger’s book from 1910-11. Her frank discussion of sex and reproduction outraged religious groups and conservatives. Image courtesy of Google Images.

Image courtesy of Google Images.

Esquire Girl Calendar 1951. Image courtesy of Google Images

Ginsberg published Howl and Other Poems in 1957. Image courtesy of Google Images.

.jpg)

Cover of ONE magazine from August 1953. Image courtesy of the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, Los Angeles, California.

.jpg)

Cover of ONE magazine from August 1953. Image courtesy of the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, Los Angeles, California.

.jpg)

Cover of ONE magazine from August 1953. Image courtesy of the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, Los Angeles, California.

Image courtesy of Google Images.

Image courtesy of Google Images.

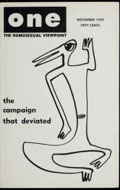

ONE cover, November 1959. Courtesy of the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, Los Angeles, California.

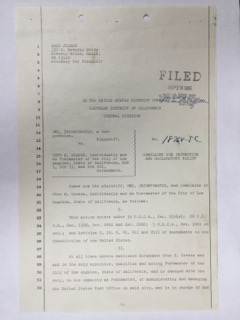

Court filing of ONE taking postmaster Otto K. Olesen to court. Image reproduced courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration at Riverside, California.

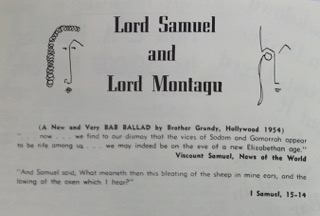

Part of page from ONE magazine October 1954. Image reproduced courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration at Riverside, California

Page from homophile publication Der Kreis. ca. 1950s. Image courtesy of Google Images.

Page from homophile publication Der Kreis. ca. 1950s. Image courtesy of Google Images.

The Supreme Court: ONE Magazine's Unprecedented Victory

Despite prevailing negative public attitude towards homosexuals at the time, and the ferocity of the lower court’s findings on ONE magazine’s case against the Post Office’s ban, Julber believed 20th-century standards of freedom of speech would prevail in the Supreme Court. However, the tiny team at ONE had little reason to expect social justice during an era, 10 years before the Civil Rights Act, when the notion of equality and tolerance was not guaranteed to racial minorities, much less to LGBT people. Sodomy was illegal in all 48 states, and the subject of homosexuality remained one that was discussed with uncomfortable derision, scorn, or as we have seen, with hatred among many in American society.

U.S. Supreme Court building, Washington D.C. Image courtesy of Google Images.

.jpg)

Publisher Samuel Roth was convicted of mailing obscene materials by the Supreme Court in 1957. Image courtesy of Google Images.

Esquire cover, ca. 1950. Image courtesy of Google Images.

Playboy cover, ca. 1950s. Image courtesy of Google Images.

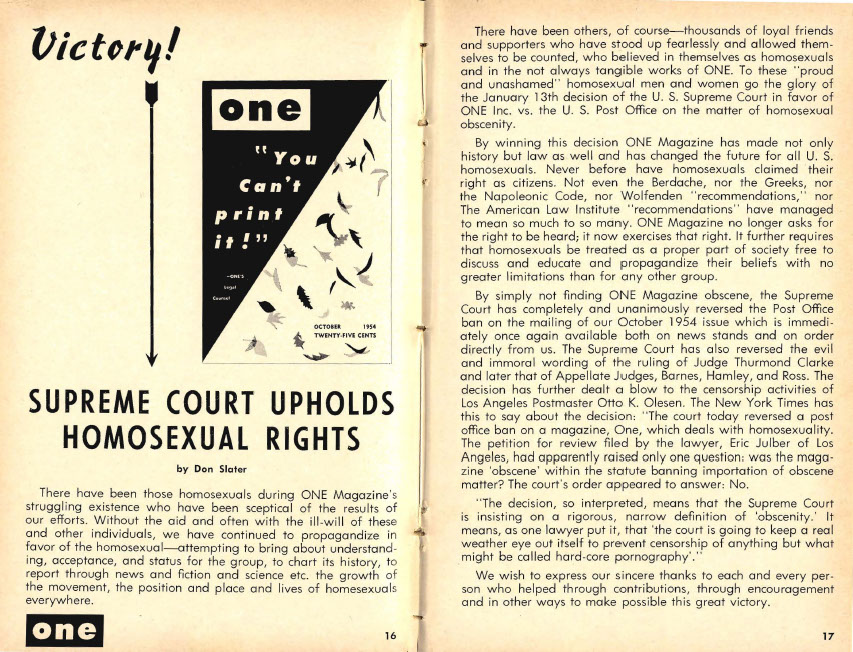

Page from ONE magazine announcing their unprecedented victory. Image courtesy of Google Images.

.

Page from ONE magazine in October 1954’s issue bearing part of offensive lesbian love poem. Image reproduced courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration at Riverside, California.

Moral crusader Anthony Comstock. No date, photographer unknown. Photo courtesy of Google Images.

Margaret Sanger was a tireless women's health advocate in the early sexual revolution. She promoted women’s reproductive education and rights, was a nurse and educator, opened the first birth control clinic in the United States. and founded the organization that would become the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. She disseminated educational information to women in articles and pamphlets she wrote through the mail. Her mailings were frequently seized or banned by postal officials.

Literature promoting women’s reproductive health and rights was a hot button issue with religious groups and right wing conservatives, and a heated topic in the obscenity in the mails debate. Her dogged determination to reach women everywhere through mailing pamphlets on women’s reproductive health issues got her indicted in 1914 for violating federal postal obscenity laws.

In 1920, the NYSSV won their obscenity complaint against James Joyce’s Ulysses, and the book was thereafter effectively banned in the U.S. until 1933, when, in United States v. One Book Called Ulysses, judge John M. Woolsey found the book to not be obscene in an important case protecting freedom of expression. The Post Office regularly burned the books throughout the 1920s.

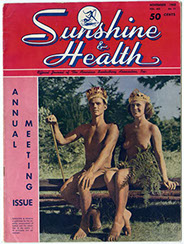

Conservatives used the Comstock Law and Postal Obscenity Laws to suppress publications considered racy, including men’s magazines, pinup calendars, erotic books and poetry, gay magazines like ONE, nudist and "beefcake" or muscle magazines.

Ginsberg’s poetry about drugs and gay sex outraged conservatives, prompting police seizures of the publication, arrests of distributors, and an obscenity trial in 1956-1957.

Many gay men relied on “beefcake” or “physique” magazines for erotica in the heavily censored postwar era. The genre influenced gay men from the 1940s to the 1970s.

Nudism was considered obscene and the lifestyle was and early issue for conservative groups attempting to eradicate what they considered subversive behavior. Nudist magazines were routinely banned along with ONE.

The editors of ONE magazine were frustrated by authorities lumping their publication together with “beefcake” and nudist magazines, after working hard to give the magazine a legitimate reputation. The ongoing harassment and double standards by postal and government authorities drove the editors to take the Post Office to court.

The establishment used precedent and continued to expanded censorship and obscenity legislation throughout the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s to attempt to block liberal writers, activists, and publishers, and to snoop into, seize, and censor the mail of private individuals. Censored and banned publications could range from men’s magazines considered racy at the time, like Esquire, to fiction like James Joyce’s Ulysses, and Beat Generation poet Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, to a gay publication like ONE magazine.

Seized private correspondence could be practically anything; postal inspectors enjoyed broad powers of interpretation on obscenity and often acted enthusiastically and with impunity against those suspected of homosexual activity.

As such, Otto K. Olesen, postmaster general of Los Angeles, seized the August 1953 issue of ONE, citing obscenity. The issue had the words, unthinkable at the time, “Homosexual Marriage?” on the cover. However, after being inspected by the FBI, it was concluded that there was nothing that could be determined to be legally obscene, lewd, or lascivious in the issue and after a few weeks, the magazine was released.

The postmaster general seized ONE again, 14 months later in October 1954. Attorney Julber received a letter from Olesen stating “he had been instructed by the U.S. Postal Dept. in Washington to detain...ONE’s October issue, pending final determination of [the] U.S. solicitor general as to its mailability.” This time the Post Office believed they had a strong case against ONE, and stood their ground. At this point the editors had had enough of what they considered harassment and a double standard, and decided to take the US Post Office to court. This was a bold and unprecedented move, as ONE, Inc., was essentially challenging the government’s right to decide whether gay people could participate in society’s larger constructs as legitimate writers, business people, publishers, and consumers.

LGBT scholar Craig Loftin states:

“ONE challenged its readers to believe that homosexuals had a fundamental right to exist in American society. They had the same rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as anyone else-not to mention rights to associate with one another, to be gainfully employed, to be treated fairly in the justice system, and to engage in private sexual behavior between consenting adults.”

The staff at ONE magazine determined they were going to fight for their rights to freedom of speech in what ultimately became the first gay Supreme Court case in ONE, Incorporated, v. Olesen. The case began in the lower courts of Los Angeles, and was the beginning of a journey that led ONE magazine to secure the first major victory for LGBT equality in US history.

The California Case

The editors and staff at ONE maintained a vigilant policy about screening every issue of the magazine for anything that could possibly be construed as lewd, lascivious, or obscene by government and Postal inspectors. Their attorney, Eric Julber, believed ONE probably was on safe legal ground as long as it discussed the ‘social, economic, personal and legal problems of homosexuals,’ and avoided stimulating ‘sexual desires.’

The fact cannot be overstated that the definition of obscenity wasmalleablel in these times. Manyconservatives, including postal and government officials, police officers, judges, and FBI agents, believed the magazine’s very existence was illegal, and anything they printed was obscene. It was illegal to be homosexual; gay people were not accepted as legitimate members of society, and therefore, a magazine for them was unacceptable.

Julber and the magazine’s editors struggled to publish a magazine that spoke truthfully about the gay experience, butthat could also could pass through the overly sensitive discriminatory checks of government censors, FBI agents, and zealous postal inspectors. There seemed to be no way they could avoid harassment, and the intense scrutiny culminated when Olesen ordered the magazine’s seizure for the second time in October 1954,callingg the material ‘obscene, lewd, lascivious andfilthy.’” Slater recalled that by that point, the editors were “tired of the uncertainty facing each issue, and were eager to take the Post Office on.” Julber offered to work, as he often did for the magazine, pro bono.

Next, they appealed to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) hoping for some“heavyweight support." They weres amazed when the ACLU refused to get involved in a case supporting the civil rights of homosexuals; it wasn’t until the 1960s that the ACLU decided to brave the negative social stigma that was associatedwith homosexuality, and joined the fight for LGBT equality.

Finally, after months of delays caused by financial problems, ONE filed suit in federal court in Los Angeles against postmaster Olesen, challenging the decision that the October 1954 issue wasun-mailable..

ONE refused to back down, and appealed to the 9th Circuit Court.

On February 27, 1957, a blistering condemnation was written against the magazine by a three-judge panel on the 9th Circuit Court branding the magazine as “morally depraving and debasing. The magazine has a primary purpose of exciting lust, lewd and lascivious thoughts and sensual desires in the minds of persons reading it.”

The panel's opinion continued, quoting a previous ruling that found that “obscenity laws are not designed to fit the standards of ‘society’s dregs,’ and that ‘It is dirty, vulgar and offensive to the moral senses.’”

The judges went on to condemn homosexuality, stating, “Social standards are fixed by and for the great majority and not by or for a hardened or weakened minority.” The judges found the magazine to be “nothing more than cheap pornography calculated to promote lesbianism,” declaring that it fails to adhere to the magazines stated mission of helping the gay community develop, to understand homosexuality, and find acceptance.

Further, they declared that the poem “pertains to sexual matter of such a vulgar and indecent nature that it tends to arouse a feeling of disgust and revulsion.” Finally, they stated that the Swiss magazine “appears harmless, but is not because it tells readers where to get more of the material found in ONE.”

The scathing written opinion of the judge's in both Los Angeles and San Francisco reflects how overwhelmingly negative public opinion was against homosexuals and homosexuality at the time. Their attitudes were likely informed by the relentless scapegoating and sensationalist press coverage of the supposed homosexual problem in America in the years leading up to the case.

ONE had failed in California, but the case was not over yet. They believed the case would prevail, and as we shall see, it did in the end, in the Supreme Court.

Days after Julber filed ONE’s petition, the Supreme Court handed down a ruling upholding the constitutionality of the federal law against the mailing of obscene material, in Roth v. United States.

This proved to be a watershed moment for ONE’s case. In that opinion, the court offered a definition of obscene material for the first time, which had previously been nebulous and used to broadly describe anything others wanted to censor. The definition stated “Obscene material is material which deals with sex in a manner appealing to prurient interest.” It further described prurient as “having a tendency to excite lustful thoughts.”

This new definition helped lawyers and legal scholars to separate sexual topics in print and their arguments more definitively than before.

Now Esquire magazine could be proven to be distinct from Playboy magazine, and ONE magazine from a gay pornography magazine. ONE magazine, full of poetry, legal advice, and editorials covering social equality issues, might now have a chance at being accepted as a magazine worthy of the mails.

The fact that the Supreme Court accepted the case is remarkable, as it would have been more likely for the court to choose to refuse to consider the case, thus avoiding the embarrassment of any mention of homosexuality in connection with the court.

By taking on the case, the justices needed to begin thinking about what homosexuality really was, and what being a homosexual truly meant to American citizens. Additionally, and of great importance, they had to determine whether the term homosexual only describes sexual acts, misbehavior, and illegal activities, and whether homosexuals were a national menace, criminals, mentally ill, or another minority group. And, did homosexual topics automatically render the content of a magazine obscene, and therefore, illegal?

Its first homosexual case split the court along predictable ideological lines between the four justices considered liberal, and the four considered conservative, and unlike most Supreme Court cases, ONE, Incorporated, v. Olesen was simply voted on. On January 10, 1958, the justices voted aloud, and, with the swing vote being made by the court’s most junior associate, who, by tradition, voted last, the court narrowly found in favor of ONE. Three days later the court issued a one-sentence unsigned ruling on ONE, Incorporated, v. Olesen:

“The petition for writ of certiorari is granted and the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit is reversed.”

The court cited Roth v. United States as precedent.

The fact that the Supreme Court would not join the federal war against gays turned out to not be front page news, in fact, mention of the victory was buried far in the back of most newspapers, further buried as one or two lines within a larger blurb about the courts concurrent rulings on two nudist magazines and other unrelated issues. But it was a victory nonetheless, and the staff at ONE was jubilant when they learned of it.

ONE’s staff and attorney had not even known their case had been accepted by the Supreme Court. Jennings and Slater were shocked when they started getting phone calls the day after the ruling from friends congratulating them on their unprecedented victory.

Slater recalled that although they were very pleased with the outcome, they didn’t have a party, although they “May have boozed it up a little more than usual…[but they were so sure of their case] the decision was sort of anticlimactic.”

The writers and editors were finally able to relax their stringent policies in their content, and the magazine continued to be published until December of 1967.

According to Jennings "It wasn’t long after that outright advocacy of homosexuality burst into being.”

They had done what had seemed impossible; the staff at ONE magazine had secured the first victory in the fight for LGBT equality in American history. The LGBT Equality Movement continues to seek justice and equality for all LGBT people, refusing to accept shame, condemnation,and victimization from those who would promote an agenda of hatred and intolerance, in large part thanks to the work of Hay, Jennings, Slater, Julber, and the rest of the LGBT Equality Movement's early champions.

Seal of The New York Society For The Suppression Of Vice. Image courtesy of Google Images.

When the case came before federal District Court judge Thurmond Clarke, the postmaster’s legal team used several examples from the October 1954 issue of the magazine’s obscenity.

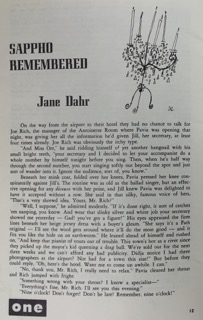

First, was a lesbian love story called "Sappho Remembered."

Throughout the story, the two women touched four times, including a passage in which “...Pavia pressed her knee conspiratorially against Jill’s.” Postmaster Olesen’s team told Judge Clarke “the story was ‘obscene because [it is] lustfully stimulating to the average homosexual reader.’”

The defense also cited a bawdy poem called “Lord Samuel and Lord Montagu,” which poked fun at an infamous scandal in Great Britain at the time in which several prominent members of the upper class had been arrested on homosexual charges. The poem’s first and last verses read:

“Lord Samuel says that Sodom’s sins

Disgrace our young Queen’s reign,

An age that in this plight begins

May well end up in flame

Would he idly waste his breath

In sniffing round the drains

Had he known ‘King Elizabeth’

Or roistering ‘Queen James’?”

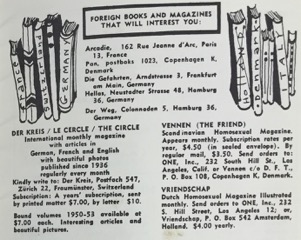

A third damning feature in the October issue of ONE magazine was an ad for a Swiss magazine, called Der Kreis, or, The Circle, in a small section on the back page called Foreign Books and Magazines That Will Interest You. It was used as part of the case because it gave information on how to obtain obscene material, meaning one could use the advertisement to order the magazine, which contained nude photographs of young men.

The lower court judges were entirely unsympathetic to ONE magazine and homosexuals in general. Finding in favor of the Post Office, on March 2, 1956 Judge Clarke handed down a decision declaring the October 1954 issue obscene...Clarke added, "The suggestion that homosexuals should be recognized as a segment of our people and be accorded special privilege as a class is rejected."

ONE magazine had lost their first battle, but they remained undaunted.

The magazine’s editors expressed their continued defiance all over the front and back covers of their next issue, with “ONE is not grateful," and "ONE thanks no one for this reluctant acceptance. As we sit around quietly like nice little ladies and gentlemen gradually educating the public and the courts at our leisure, thousands of homosexuals are being unjustly arrested, blackmailed, fined, beaten, and murdered.”

Part of page from ONE magazine October 1954 advertising European dealers in gay literature. Image reproduced courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration at Riverside, California.