The ONE Exhibition,

The Roots of the LGBT Equality Movement

ONE Magazine &

The First Gay Supreme Court Case In U.S. History

1943-1958

Police Entrapment

The founders and publishers of ONE magazine wanted to discuss important topics for gay men and lesbians at the time, such as vice squad sting operations, police brutality, and entrapment.

A defining feature of the magazine was the fact that it focused on social and legal issues caused by the institutionalized attacks with the intent of helping gay people navigate the legal system, which was stacked against them.

The first issue, published in January 1953, featured a story about founder Dale Jennings’ entrapment. It contained this advice, meant to inspire those would-be victims of the police to stand up for themselves, a concept that was foreign at the time:

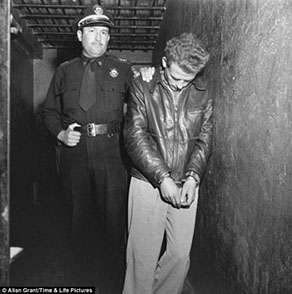

Man under arrest in 1951. Photo courtesy of Google Images

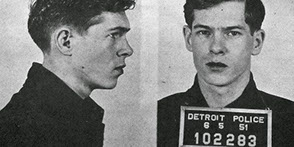

Mug shot of 1950s music idol Johnnie Ray, who was arrested as he was leaving a gay bar in Detroit. Gay bar raids were common for many years across the country. Photo courtesy of Google Images.

When Jennings was arrested, the other members of the Mattachine Foundation rallied in his support. They gathered funds to hire a lawyer, produced leaflets as the "Citizens Committee to Outlaw Entrapment," and distributed them in neighborhoods with high densities of gay residents. With their help Jennings’ case was eventually dropped, but only after Jennings admitted to being a homosexual in court, and denied the charges against him, thus setting a precedent for the gay community to stand up for themselves.

Jennings wrote about his entrapment for the cover story in the 1st issue of ONE magazine, summarized below:

The evening began innocently enough with a trip to see a film. Around 9 in the evening, he walked past several theatres that didn’t have films playing he wanted to see, and he was headed to a third theatre. Then, after using a public restroom in a park, he was followed by a “big rough looking character who appeared out of nowhere.” This person followed Jennings, attempting to engage him in conversation, and followed him into the theatre. Jennings didn’t want to see the film, but went into the movie in hopes that the man would leave him alone. However, the man waited in the theatre, and followed him out, and over a mile back to Jennings’ home; Jennings described trying to shake the person off his tail, but with no luck.

Jennings tried to tell him good night, but the man pushed his way inside, flopped on his sofa, and began asking questions about his work and how much money he made, after which he went into the bedroom, sat on the bed and unbuttoned his shirt. Jennings actually thought the man was a thug who was going to try to rob him. He wanted to call the police, but knew that might make matters worse. The man demanded that Jennings join him in the bedroom, after which he accused Jennings of being a homosexual and tried to get him to engage in physical contact, an invitation that Jennings repeatedly rebuffed. Finally, the man grabbed Jennings’ hand and shoved it down his pants, thereafter handcuffing him and dragging him out of his house. Jennings was marched through the city streets, back to the park where the undercover vice cop found his partner. They put Jennings in the patrol car and interrogated him. At one point one officer remarked to another that things had been so dull that week that it was all he could do to “keep up with the quota.”

When the case went to court, Jennings admitted to being a homosexual, but denied the accusations against him. The jury deliberated for forty hours before asking to be dismissed; all but one had voted for acquittal, with one declaring that he would “hold out till hell froze over” for guilty.

The district attorney eventually dropped the case. It served not only to galvanize the founders of ONE against the oppressive forces being used against the gay population at the time, but also established a precedent for the community for those who were willing to fight against the system in the early LGBT equality movement

ONE published stories, letters, and editorials that were meant to promote critical thinking among their readers, and to highlight the political and social implications of the organized police activity used against them.

This excerpt shows the first few lines of a powerful essay, published in May 1953, signed with the initials M.B. Aliases, anonymous submissions, and simply using initials was a common practice at the time, when one could lose everything if a neighbor, coworker, spouse, or family member discovered an individual was writing into a gay publication.

As we have seen, the FBI was also investigating many of those involved in such endeavors, leading many to seek anonymity. The essay dramatically illustrates the frustrations many gay men experienced:

"We live in a world of fear: we fear revelation, we fear publicity, we fear knowledge and we fear detection. We live in a world of criminality and we foster that criminality: at one price or another we purchase privacy, we purchase love, we purchase fear".

Further, many letters the editors received cried out against the social injustice the writers experienced:

"...Something must be done. The Vice Squad is terrible in Los Angeles; I am from New York City and can’t seem to see the difference between the Gestapo of Germany and the Vice Squad of Los Angeles. No one is safe here or has any rights…"

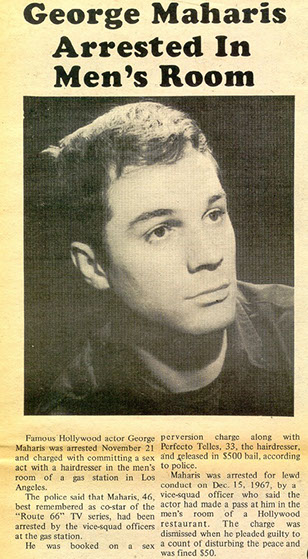

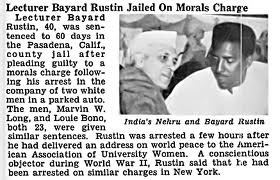

Newspaper article featuring story of arrest of actor on morals charges in 1950s. Image courtesy of Google Images.

Article about arrest and conviction of civil rights leader Bayard Rustin on morals charges. Image courtesy of Google Images.

A Fledgling Community

ONE’s editors received hundreds of letters every year from readers all over the country, and to a lesser degree, from around the world. The letters cover a broad spectrum of attitudes and experience, and only a small percentage was ever published. This was partly due to the fact that the editors were concerned about protecting the legality of the magazine, its image as a legitimate publication (devoid of salacious or inappropriate content), and therefore its mailability.

Many wrote in thanking the magazine for the important work they were doing, while others expressed animosity, distaste, or even negativity about the existence of a magazine for homosexuals.

Others wrote heartbreaking letters describing their isolation, or about the loss of their families after being discovered or coming out, or, in a few cases, about all the fun they were having, and how great it was to be gay.

Some wrote in demanding more exciting content, too, and described their longing for access to gay erotica.

There were occasional disturbing letters from disapproving and hateful people who had come across the magazine as well. Their letters in particular highlight the disgust and scorn many felt for gay men and lesbians, and how the national anti gay propaganda machine of the government, religious leaders, and the press, led them to feel free to tell them so in no uncertain terms.

In many cases there was no where else for gay men and lesbians to write to, no one else to voice their fears and concerns to, or to be honest with about significant issues in their lives.

As such, ONE was truly a lifeline for many. Some urged activism, while others disagreed with the concept of the founders, and wanted to be left in the shadows.

Dorr Legg at the piano. Undated photo Courtesy of the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, Los Angeles, California. Photographer unknown.

Excerpts from ONE Magazine, and "Letters to ONE" by Craig M. Loftin

“Gentlemen:

While at a party last night my host slipped into my hands your January issue of ONE. I sat right down and read it cover to cover. I cannot tell you how deeply moved I was when I finished. Mr. Cory was right when he said our number is legion, but it’s very clear to me that only in organizing, as you have done, can we ever hope to progress out of these Dark Ages of injustice and ignorance.

K.R., Idaho”

“Editors:

Why in hell are you idiots drawing attention to us by starting a magazine? Prejudice will fade away all alone if we don’t make things worse by fighting it.

Savannah, Georgia.”

“Dear Sirs,

I came out in homosexual life at the age of eighteen. Now I’m nineteen and think that it’s a very happy but lonely life. A lot of times I feel like committing suicide, but I shouldn’t be so cowardly as to do anything like that.

I guess the best thing for people like us is to keep busy going to college or studying. I do hope someday that I won’t be lonely any more. Your magazine is terrific and I pick up a copy each time it comes out.

Sincerely,

Richard”

“Dear Editors:

It takes great courage to do so well the task that you’ve undertaken; plus immense compassion for your fellow man-to be quite willing to help splinter the moral bigotry that imprisons our so-called ‘enlightened’ society. Maybe if I had known of your publication a year ago, a dear friend of mine would not have taken her own life-if she had felt that there was some slim chance of one day being both understood and accepted.

[no name published]”

“Dear Sir or should I say She:

I happened to come across this magazine today. I found it in his belongings. There’s no doubt about it I have a brother who is homosexual, and I hate his guts for it. He never tried to pull anything on me and better not. I read one of his queer magazines and think whoever publishes it and whoever reads it has to be queer! I think the stuff you write in those books is a bunch of B.S.

I met a few homos not too long ago. They tried to take advantage of me. However, I got in a struggle with two of them. I had a chain and wrapped it around both of their queer necks.

That’s how I feel about fairys [sic], queers, homos-whatever you want to call them. How can a man have sex with another man I’ll never know and don’t care to know. The same goes for the women. If I ever meet up with any more I’ll use my .38 on them. That’s what they deserve.

A Straight Guy

P.S.: I’ll expose you all! Ha, ha, you queers.”

~

~

~

~

Dale Jennings and his friends in the Mattachine Society stood up to the corruption of police when he was unfairly entrapped by an L.A. vice squad, and won. The courage Jennings and the Mattachine Society displayed in standing up to the system served as a platform from which the first gay magazine in the United States sprang. As such, the founders of the magazine became the first voice for the LGBT Equality Movement.

Gay people often faced great hardship and isolation because of their sexuality. Many longed for community, and the camaraderie that comes with discussing common interests and experiences. Through their magazine, the founders of ONE sought to establish a common language and community for gay men and lesbians for the first time.

For many gay people in the era, there was no support system to reach out to. ONE magazine provided an outlet through the "Letters To ONE" section. Photo courtesy of Google Images.

“Officers of many vice squads and vagrancy details are given what amounts to free reign to pursue, entrap, and arrest not only any who are unwisely human enough to succumb to their well designed plots and impersonations, but those who are erroneously suspected. The reason that these persons are such easy prey and that the police get by without complaints filed against them lies in the sordidness of the accusation itself which the victim wants hushed up at all costs.”

Additionally, they published legal codes and definitions with explanations that were intended to help gay people understand the laws that were being used against them with such success.

The excerpt above, from an editorial titled "The Law", was followed by the legal definition of entrapment from the Summary of California Law:

“Entrapment. The defense of entrapment is available where the crime was not contemplated by the defendant, but was actually planned and instigated by police officers, and the defendant was by persuasion or fraud lured into its commission.”

Jennings’ entrapment case became a catalyst for the magazine’s founders, and he wrote a story about the experience for the first issue of ONE Magazine.

The tone is unrepentant, and bitter. He describes the case as typical of the time, and discusses the unfair judgment of his heterosexual friends as well as his homosexual peers, who believed that if gays acted with appropriate restraint, avoided dangerous situations and scandalous persons and locales, gay men could be safe from persecution.

As such, according to Jennings, many people felt that those accused of deviant crimes deserved what came to them for not adhering to acceptable behavior patterns laid down by respectable society and the police.

Through his writing and activism, Jennings sought to clarify for the magazine’s readers the futility of accepting the status quo.

It was the merciless tactics of the police, from the entrapment of gay men with the vice squads, to brutal beatings in gay bars, as well as their harassment in the parks and on the streets of cities all across the United States that drove the founders of ONE magazine to fight back.

The unfair firings and discriminatory policies of the government were other important factors. Because of all of these issues and more, the Mattachine Foundation had recently been established, but Dale Jennings’ entrapment by Los Angeles police galvanized the movement, and thus, ONE The Homosexual Magazine was born as this small group of courageous activists struck out, against all odds, to try and improve the lives of gay people everywhere.